- Home

- Thomas H. Pauly

Zane Grey Page 2

Zane Grey Read online

Page 2

Grey also avidly pursued saltwater fishing in Tampico, Mexico; Long Key, Florida; and Catalina, California. During the 1920s, his lust for “virgin seas” and his determination to catch the biggest fish carried him to Nova Scotia, the Galapagos Islands, New Zealand, Tahiti, and Australia. These trips garnered him a dozen world records; he was the first person to land a 1,000-pound fish on sporting tackle. His nine books about these adventures, all entitled “Tales of …,” contain some of his best writing; they remain in print and deservedly so.

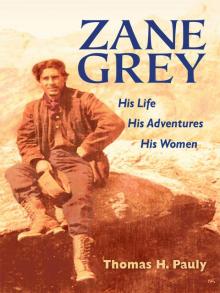

Grey in Arizona, 1920. (Courtesy of Loren Grey.)

Left to right: Mildred Fergerson, Lillian Wilhelm, Claire Wilhelm, and Zane Grey at Long Key, 1916. (Courtesy of Pat Friese.)

For a person of such range and accomplishment, it is remarkable that his life remains so little-known and misunderstood. Currently, the chief source of information is a biography that is outdated and long out of print—Frank Gruber’s Zane Grey: A Biography (1970).9 Gruber started his project as an ailing author of popular Westerns and actually died before the biography was published. Gruber made little effort to distinguish the specious and anecdotal from the true; important information was sloppily handled and intentionally ignored. Gruber was also recruited to write this biography by the Grey family, which pressured him to uphold the wholesome image of the author promoted by his publishers and to gloss over or suppress the problematic aspects of his life.

Grey had a troubled youth, and he was deeply scarred by his father’s slide into poverty and his family’s decline from its distinguished heritage. As a young man, he was sensitive, reserved, and antisocial, and later he became outspoken and reactionary. He disliked cities, vehemently opposed drinking and smoking, and repeatedly criticized modern development.

Grey was profligate with his money and often used overspending as an incentive to work. In 1913, after renting a spacious apartment in New York City for the upcoming winter, he wrote to Dolly, “I’ve got to touch Rome [Zane’s brother] or somebody for some coin, and then work like hell and I’m grimly settled in mind on the latter.”10 By 1920, when his annual income surpassed $100,000, he was so pleased with his two-year experiment with California living that he purchased a grand residence in Altadena. That same year, he acquired another house in Catalina, a ranch in Arizona, and an expensive new boat. Five years later, when Zane purchased a grand schooner and initiated costly renovations, Dolly indignantly wrote to him:

Now about the ship. Never knew you were even looking at more than one so your telegram was somewhat puzzling. However, the part about depositing the $10,000 for you by Sept. 1st was clear enough. I’ll do it, tho it will pretty well clean me out. Not a cent came in since you left and the only money you have given me in months is that $9,000 just before you left … According to the N.Y. Times you are having your boat refitted in N.Y. Why? When labor was so infinitely cheaper in Nova Scotia? Did anyone ever tell you that it would cost you a fortune to bring that boat through the canal? It cost the Manchuria $11,000 for a single trip. Well, Pa’s rich and Ma don’t care! That is, if the children don’t starve.11

Her irony and ire could not constrain his determination to have what he wanted.

Zane Grey in front of the house in which he grew up, during his 1921 visit to Zanesville. (Courtesy of Loren Grey.)

By the Depression, Grey’s profligate spending was so ingrained and so excessive that it almost ruined him. Despite widespread signs of a national financial crisis, an unmistakable drop in demand for his work, and objections from his wife, he purchased another yacht for $50,000 in 1930 and then spent $300,000 on renovations. This would be approximately three and a half million in today’s dollars, but an even better measure of this sum might be the $80,000 that Babe Ruth earned in 1931, a salary that provoked controversy because he was paid $5,000 more than the president of the United States.12 Added to the debt that Grey was already carrying, this yacht decimated his finances and necessitated that he cut short his most ambitious fishing trip, intended to circle the world. For the next four years, he hovered precariously close to breakdown and bankruptcy.

Over the course of his life, Grey also offended many people. He so antagonized members of the prestigious Tuna Club in southern California that they conspired to drive him away. After the citizens of New Zealand staged an extravagant welcome for him on the occasion of his visit, he publicly denounced their primitive methods of fishing. When Arizona refused him a special exemption from its hunting regulations, he angrily proclaimed that he would never again return to the state in which so many of his novels had been set. Inevitably, and inexorably, his dark moods, competitiveness, and self-absorption drove away almost everyone he ever befriended. Laurie Mitchell served him longer than any of his other boat captains, but his seven years of loyalty did not prevent Grey from summarily firing him. Grey was so grateful to Alvah James for his example and advice when he started out as a writer that he allowed him to occupy his Lackawaxen residence for years, but his abrasive letters to James suggest that their friendship only endured because they were never around each other. Grey’s deep attachment to his younger brother extended from childhood outings through many trips together as adults, but even R. C. eventually had to distance himself.

Dolly was the one person who remained steadfastly loyal to Grey, and her observation to Beard that it took “great genius to recognize one of [Zane’s] ilk” was at once self-congratulatory and characteristically self-effacing. She understood better than anyone else the full measure of her husband’s uniqueness and its staggering demands. During their courtship, she initially won his love by supporting his ambition to write and allaying his crippling doubts. In one of his earliest letters, Grey wrote to her:

On the stone I shall engrave:

Here lies a man, to fame unknown;

Who on the wings of love was blown,

To suffer for the sins he’d sown.

What an epitaph for the greatest might-have-been in American letters.13

Dolly approved of Zane’s wrenching decision to quit dentistry and ably assisted his ferocious struggle to get his work published. Her modest inheritance financed the two Arizona trips that transformed him into an author of Westerns.

Dolly accommodated herself to “those adventurous trips he loved so much.” From the East in the spring of 1922, Zane wrote to her: “We are not going to see a great deal of each other this year, I’m sorry to say. And this letter is to ask you to help me make the best of what we have. A little time in April—in August—in November.”14 His ensuing voyages to New Zealand, Tahiti, and Australia kept him away six to nine months each year thereafter, and much of his time back in the United States was also spent away from home.

Most extraordinarily, Dolly accepted “the girls.” With this, more than with all the other things that she did for Zane, she demonstrated that she possessed the “great genius to recognize one of his ilk” and that her genius was as peculiar as her husband’s. Grey was extremely handsome and charming to women. He had many sexual adventures while growing up and during his years as a baseball player. At sixteen, he was arrested in a brothel, and several years later he was charged with a paternity suit. He had affairs with other women throughout his five-year courtship of Dolly and after their marriage. In 1913, he took two female cousins of Dolly on his first trip to the Rainbow Bridge, perhaps the most memorable trip of his life. With an outfitter he trusted and an Indian who pioneered the route, he and his companions traversed a labyrinth of canyons and treacherous terrain in northern Arizona to a remote natural arch first seen by whites only four years before. He perceived the awesome Rainbow Bridge as validation for the adventure in his novels, for the spiritual transcendence he associated with the West, and for his yearning for romance.

Thereafter, women regularly accompanied him on his trips, sometimes as many as four. The few scholars aware of these relationships have assumed that they were paternal and platonic,15 but they were, in fact, romantic and sexual. There exists an enormous, totally unknown cache of photogra

phs taken by Grey of nude women and himself performing various sexual activities, including intercourse. Of the women discussed in this book, only Nola Luxford and Lola Gornall are not in this collection. These photographs are accompanied by ten small journals, written in Grey’s secret code, that contain graphic descriptions of his sexual adventures.16

Dolly knew about these relationships and accepted an “open marriage” long before the term existed. She and Zane never divorced and each professed love for the other up to their deaths. Their marriage was not only unusual, but also crucial to his fragile health and his success as a writer. Dolly supervised the business side of Zane’s career for years, and her decisions averted bankruptcy during the 1930s. She accepted his suspect claims that his trips and women alleviated his depressions and inspired him to write. Although these affairs provoked considerable anguish and sharp-tongued complaints, Dolly consistently accepted them, sometimes in ways that were remarkable. She remained close friends with some of his companions, and even allowed several to stay in her home. She intervened on Zane’s behalf when the romances foundered, and maintained friendships with some of these women for many years after his death. She was faithful Penelope, steadfastly loyal to her restless, driven Odysseus.

Obviously, Dolly was an unusual woman, and most of the “other women” were too. Contrary to the easy assumption that they were foolish, weak, or exploited, Grey’s paramours were usually vivacious, outgoing, broad-minded, and unconventional. In an era when marriage was the rule and alternatives were limited and unappealing, these women chose to be different. They had a relish for adventure that Dolly lacked, but admired. Their openness to sex came with an enthusiasm for primitive conditions and outdoor sports that only men were supposed to like. Grey’s published accounts of his adventures seldom mention these women, in part to mask his involvement with them, but also to uphold the prevalent belief that outdoor sports were a male preserve.

If the unusualness of these women was greatest in their capitulation to Zane’s needs and wants, none was as accepting as Dolly. Some balked at his uncompromising need for others. Some needed other partners too. Some objected to the time he spent away from them; others were offended by his returns home. Some could not endure the inconsistency of his attention to them; others left because of the stifling heat, seasickness, and poor food. Dolly outlasted them all because she best understood Zane and effectively used her knowledge to help and hold him. She realized that human nature, common sense, and the world conspired against his grandiose dreams. As she once confessed to a mutual friend: “I must admit that I am looking at the book [a new Zane novel] through the bias of Zane’s hurt. Don’t laugh! The man has always lived in a land of make-believe, and has clothed all his own affairs in the shining garments of romance, and it is as if these were rent and torn and smirched.”17

Zane’s depressions were such that, had he yielded to them, they could have prevented him from completing a single novel. That he endured so much anguish and completed so many books is remarkable. Set against his enormous investment in trips and women, his output is amazing. Grey’s unquenchable need for escape, inspiration, and romance kept him searching for more Rainbow Bridges. Dolly accepted his women and travel as necessary and therapeutic, but she also realized that they could aggravate his depressions, and did so many times. Thus when her Ulysses returned with his garments “rent and torn and smirched,” loyal Penelope put aside her misgivings and repaired the damage so that he could resume his unending quest.

1

Wayward Youth: 1872–90

“We all have in our hearts the kingdom of adventure. Somewhere in the depths of every soul is the inheritance of the primitive. I speak to that.”

—My Own Life

Pearl Zane Gray’s pioneer heritage was imprinted on his consciousness with the name his parents gave him at his birth on January 31, 1872. Anecdotal histories report his given name of Pearl as derived from the mourning attire of Queen Victoria that newspapers regularly described as “pearl gray.” Although Pearl may also have been named after a distant relative, his unusual, female name caused much taunting and embarrassment. Eventually he dropped it, though not until his twenties, and long after the spelling of his last name had been changed from Gray to Grey. His middle name of Zane, by which he would be known as a writer, did come from his family background. His mother was a Zane—and proud of her family lineage that extended back to Ebenezer Zane, a patriot colonel during the Revolutionary War, and his heroic sister Betty.

Although Grey believed that his ancestry was Danish, Robert Zane, a Quaker, carried the family name to the New World in 1673 from England, and he resided at various locations in New Jersey. His grandson William Zane chose to marry outside the religion and he was so ostracized that he relocated to Hardy County, West Virginia, not far from that state’s current border with Virginia. Ebenezer, William’s second son, was born on October 7, 1747, and three more sons followed—Silas, Jonathan, and Isaac. The Zane brothers became explorers and quickly adapted to the fluctuating alliances of local Indian tribes—mainly the Wyandots and Delawares. Around 1757–58, Jonathan and Isaac were kidnapped by Indians and lived with them for several years. Following a successful escape, Isaac returned and married Myeerah, the daughter of a Wyandot chief.1

In 1768, Ebenezer married Elizabeth McColloch. She and her four brothers, who were also adept woodsmen, were reputed to be half-Indian and instilled in the young Zane a lifelong belief that he carried Indian blood.2 A year later, following the birth of the first of the couple’s twelve children and ratification of a treaty that opened southeastern Ohio to settlement, Ebenezer, Silas, and Jonathan explored and claimed two miles of property on each side of the Ohio River near Wheeling, West Virginia.3 In 1770, Ebenezer brought his family to Wheeling, and he participated in the construction of Fort Fincastle there in 1774. During the Revolutionary War, he led a successful defense of the fort, renamed Fort Henry, against several British and Indian attacks. A final assault on September 12, 1782, exhausted the defenders’ stock of gunpowder, and Betty Zane saved the day by running a gauntlet of gunfire and returning with a new supply.4 Grey’s first three novels would memorialize the heroism of these distant relatives.5

Following the Revolutionary War, Ebenezer hunted and did little to develop his property. A New England merchant who visited him in 1789 observed that he made “money very fast but live[d] poor.” Twenty years after his original claims, his holdings were still characterized as “fronttear,” and he had acquired a bad reputation for his foul temper.6 When his seventeen-year-old daughter Sarah received a marriage proposal from John McIntire, who was eighteen years older, Ebenezer forbade the marriage and huffed off for an extended hunting trip. During his absence, the two married anyway.

Despite these faults, Ebenezer stayed vigilant for commercial opportunity. He shrewdly perceived the 1795 Treaty of Greenville as a golden opportunity for “a good Wagon road.” He petitioned Congress to establish a major throughway from Wheeling, West Virginia, to Maysville, Kentucky, and to compensate him for his military service with parcels of land suitable for ferry crossings on the Muskingum, Hocking, and Scioto rivers. Approval of these requests in 1796 produced two memorials to his name—Zane’s Trace and the town of Zanesville on the Muskingum River. Ensuing modification of the original route, along with extensive improvement over the next twenty years, created the National Road, the country’s first highway. The National Road established Zanesville as a commercial center for outlying farms, and it remained so when Zane’s parents moved there around the time of the Civil War.7

Alice Josephine Zane, Zane’s mother, was born on September 5, 1835, to Ebenezer’s son, Samuel Zane, who inherited property from his father in Ohio across the river from Wheeling.8 Little is known about Samuel’s life beyond entries in local records that eleven of his twelve children were born there and that he served for several years on the local school board. Alice met her future husband, Lewis Gray, when she was visiting a sister who had married a

nd relocated to Westmoreland County, where Grays had worked as farmers for several generations.

Liggett Gray, Zane’s paternal grandfather, grew up in Westmoreland County, and resettled to a farm near Zanesville shortly before his marriage to Nancy Guttridge on April 3, 1816.9 In June of the following year, they had the first of their thirteen children. Lewis, their eighth child, was born July 10, 1831.10 He and his three older brothers worked Liggett’s farm with the expectation that they too would be farmers. The two children who preceded Lewis and the one who followed were daughters, and a brief family history written years later by Ida Grey, Zane’s sister, claimed that Lewis was “petted and spoiled” by his sisters.11

Lewis undoubtedly met Alice Josephine through relatives in Westmoreland County. They married on February 5, 1856, and did not have their first child until five years later.12 Their life together was a far cry from the eventfulness and glory of Ebenezer’s. Ida’s family history claims that her father owned a “fine farm” at the time of his marriage, but sometime around the birth of their first son Ellsworth in 1861, Lewis made a momentous, life-altering decision that foreshadowed a similar one by Zane: Lewis hated farming so much that he quit to become a dentist instead. Prior to the Civil War, dentistry was more a trade than a profession, and so Lewis moved to Zanesville to apprentice himself to John Hobbs, who had been a gunsmith prior to taking up dentistry.13 When he completed his training, Lewis opened an office on Main Street. Though he changed his Main Street address several times, he remained in Zanesville for the next thirty years, and his next four children were born there. Ella (1867), who came a year after Ida (1866), was beautiful and a favorite of her parents, but she died suddenly on February 7, 1871. An entry in the record book of the town cemetery communicates the family’s grief with its notation that she was “four years and twenty days old.”14 Pearl Zane Gray was born a year later on January 31, 1872. Romer, nicknamed “R. C.” and Zane’s closest friend for many years, followed on April 8, 1875.

Zane Grey

Zane Grey